Zines are small, typically self-published booklets usually focused on a niche subject. These little publications, small in scale and specialised in scope, have historically been important in the literary history of marginalised communities, whose writers and artists have used them to express their lived experiences and pursue shared goals through diverse mediums such as poetry, fiction, comics, and more. They’re an important form of knowledge production – especially for queer folks whose narratives are often absent from mainstream literature, whether academic or otherwise.

Over Pride month 2025, a group of Dalit and Bahujan queer individuals came together to launch a collective zine emerging from the messy, raw, and radiant geographies of queer-caste life in Delhi. As a collective project, it explores oppressed-caste queer urban geographies through community-led, collaborative research practices, anchored in storytelling. These stories challenge dominant urban planning discourses, and reveal how everyday spaces like the nala - the open drain - are imbued with the politics of caste. For the creators, this took shape as a form of queer methodology and resistance against institutional norms, eventually becoming the zine ‘Across the Nala.’

Reimagining Delhi through storytelling from the fringes

Zine-making to reflect queer experiences isn’t a new phenomenon. This zine comes a decade after three Dalit queer individuals – Dhiren Borisa, Akhil Kang, and Dhrubo Jyoti – read out the first-ever Dalit-Queer manifesto at Delhi Queer Pride in 2015. “Across the Nala” extends this historic moment by foregrounding the experiences of Dalit Bahujan queer folks in a city that is largely seen through a caste-blind lens. It reimagines the city of Delhi and creates space to show how Dalit Bahujan queer people live, and desire, in the city.

The zine is illustrated by Rishabh Arora, and features powerful portraits, memoryscapes, and mapped experiences of Delhi, offering a fresh lens on familiar locations. The colour palette remains rooted in Ambedkarite blue, pink, and splashes of white.

When we think of a nala, we often imagine black, untreated sewage with its rotten stench. When we think of Delhi, we picture monuments, gardens, and Connaught Place. When we think of queerness in Delhi, we might recall clubs or the Jamali Kamali tombs or queer collectives at the University of Delhi. This zine reimagines queerness in Delhi through lived experiences that many choose to unsee as our larger imagination of the city is limited to key spaces – we focus so much on the centre that we forget who lies on the fringes. It is also dedicated to the Sahibi River, a Yamuna tributary that runs through Delhi, beginning from Dhansa village.

The zine asks many questions of the city, and of you, as the reader. When you walk through Delhi, or march in the Delhi Pride parade, do you really see the city as it is? In Khuswant’s City Limits, a story that features in the zine, we see Delhi for what it is – not just urban, but deeply rural in parts. Similarly, another story, Arya’s Place of Unravelling critiques caste blindness in urban life, describing how they had to learn which parts of a city like Delhi allowed them to be themselves. They also reflect on the importance of contributing to knowledge production rather than remaining mere consumers.

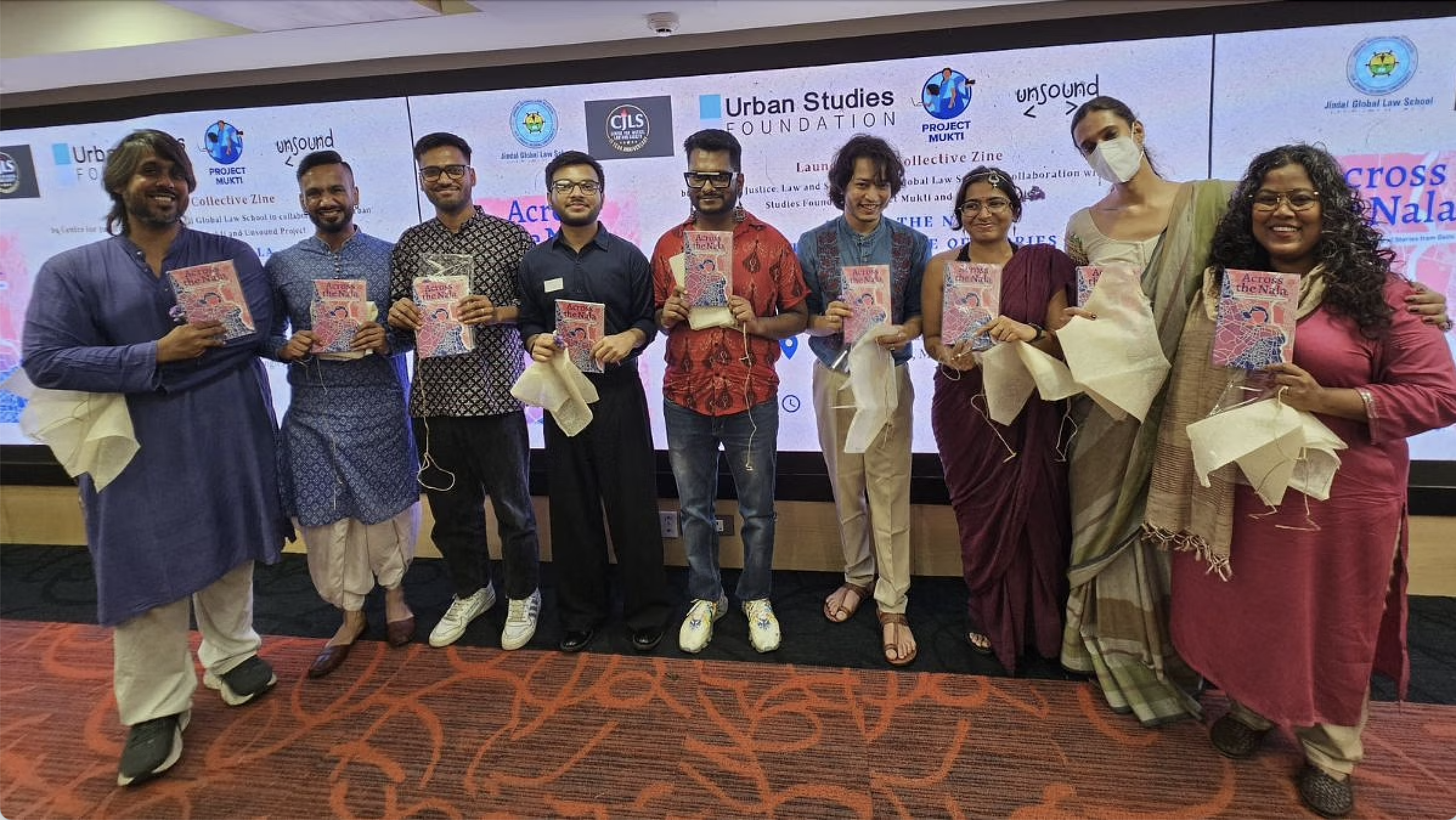

(L-R) Dhrubo Jyoti, Dhiren Borisa, Jatin Pawar, Arya, Neeraj Kumar, Saurav, Bhumika Saraswati, Vqueeram, Sanghapali at the launch of the zine ‘Across the Nala’ in New Delhi | Image Source: The Print

Belonging, Aspirations and Negotiations

When queer people move to cities like Delhi, they make many negotiations. Choosing queerness often means attempting to escape caste. There are multiple tensions between the aspirations and realities of being queer and Dalit Bahujan in a city like Delhi. This includes the struggle for housing, livelihood, and the everyday politics of being seen. We see this in Rajouri Ka Nala, where Neeraj reflects on how silver jewellery made them feel more accessible but living near a nala meant needing better care for it, as the jewellery would easily tarnish.

This also ties in with another narrative in the zine, Jatin’s Nala Paar Sisters, where one line reads, “A gay without an iPhone is not gay. Not a real gay.” In the world of social media, where photos act as currency in dating spaces, the ability to post high-quality pictures in places that look expensive becomes a marker of identity. While that might not necessarily dictate a person’s socio-economic status, it does show aspiration, and how expression relates to association with a higher class. This recalls how, during the pandemic, many students were ashamed to turn on their Zoom cameras because they didn’t live in ‘modern’ homes or had separate study rooms. Becoming ‘queer’ often involves an ‘unbecoming’ through/of one’s caste identity.

There is an everyday struggle in belonging, and aspiration is what the collaborators in the zine were asked to think about. During the workshop that led to the making of the zine, they brought objects and memories that helped them hold onto the city and helped them make sense of their queerness; following a journey of viewing queerness as fragile mythmaking. Writing for Queerbeat, Sudipto Das reflects on the zine, saying: “For us caste-oppressed queer folks, queerness is so much about navigating the messiness of this in-between, the never-ending oscillation between our realities and our aspirations.” This never-ending oscillation is where authenticity lies for queer storytelling.

Delhi as a Site of Violence

The narratives in the zine tackles violence in the making of a city by not only reflecting on how queerness is aspirational, and how desirability is shaped by one's locality, their phone model etc. but also by how they describe their address, and the struggle that goes in the making of a city. Saurav’s Pin Code connects pollution not just to air or water, but also to the breakdown of community-oriented spaces. While Delhi offers room for queerness and sexual freedom, it lacks the communal rootedness of their hometown in Jharkhand. Their dream is to have a simple address like “6, Lodhi Road,” rather than one that requires micro-directions to be found.

In Burnt Paper, Bhumi depicts Delhi as a site of violence, especially against minorities and dissenting voices, with a focus on attacks on university spaces in the past few years. Adding to this, Aishwarya’s Cactus explores what it means to seek belonging within institutions with anti-Mandal histories. They compare being a cactus to being neurodivergent and queer, i.e. people who are often seen as a nuisance. Their hope lies in Begumpura, the utopia envisioned by Bhakti poet-saint Ravidas, where everyone can be themselves. Inji’s City of Contradictions also traces how Ambedkar’s philosophy became their anchor, giving them voice and clarity.

Alienation in Queer Spaces

A couple of narratives dive right into the alienation in queer spaces. M’s Where is Home? delves into the duality of acceptance and alienation – while the city offers anonymity and freedom, desire is still marked by class and wealth, excluding many. Even within friendships or shared homes, community-building requires time and labour.

The zine closes with Vasu’s Hickey Skin, where the title refers to how hickeys don’t show on their darker skin (drawing a sharp parallel to Toni Morrison’s The Bluest Eye). Their piece maps Delhi through deeply personal landmarks – college, a favourite chai spot, places of support, college library; and this is intertwined with a map of their own body, a mapped portrait of how they see themselves. Their contribution also reflects on how shame around skin colour was inherited via their parents and communities and how they eventually grew to love the city.

‘Across the Nala’ is a vital reflection which maps crucial pieces of Ambedkarite history which are amiss from the normative construction of cities like Delhi. It challenges us to look beyond familiar ideas of the city – as a cultural melting pot, a queer haven, or a capital of inclusion; and to reckon with what truly makes any space liveable and truly inclusive for Dalit Bahujan queer folks.

To know more or order a copy of the zine, you can write to dhirenborisa6@gmail.com.

Text by Rajeev Anand Kushwah. Rajeev is a researcher-writer interested in queer experiences, the feminist ethics of care, and masculinities.

When queer people move to cities like Delhi, they make many negotiations. Choosing queerness often means attempting to escape caste. There are multiple tensions between the aspirations and realities of being queer and Dalit Bahujan in a city like Delhi. This includes the struggle for housing, livelihood, and the everyday politics of being seen. We see this in Rajouri Ka Nala, where Neeraj reflects on how silver jewellery made them feel more accessible but living near a nala meant needing better care for it, as the jewellery would easily tarnish.